This morning, the Parliament of Portugal hosted for the first time since the Carnation Revolution ended the dictatorship on April 25, 1974, a solemn session of tribute to the events that occurred 19 months later, on November 25, 1975, which meant the end of the turbulent revolutionary period. The event, marked by controversy due to the rejection it inspired both in former soldiers who participated in it and in left-wing parties, served to confirm the radicalization of the speech of André Ventura, the president of the far-right party, Chega, against immigration, which has become the central axis of his political action.

He also did so this morning when comparing “the threat of a Soviet dictatorship” in Portugal 49 years ago with “the new real threat of uncontrolled immigration.” “It destroys our country and our identity,” he said. After highlighting November 25, 1975 as “the true day of freedom,” he blamed foreigners for “many sexual crimes” without offering figures to support that claim. And again he referred to the event that ended with the death of Cape Verdean Odair Moniz, shot in October by police officers in a neighborhood in the metropolitan area of Lisbon. “49 years later, the peripheral neighborhoods of Lisbon and Porto present new threats and the country prefers to agree with criminals than with the security forces,” he said on the platform.

The death of Odair Moniz, 43, is under judicial investigation, although the officer who shot him already acknowledged that the victim was not carrying any weapon when he got out of the car after being chased by the police. Moniz had a cafe in the Zambujal neighborhood and no pending charges with the justice system. Several socialist deputies left the chamber while Ventura attacked immigrants and the political system. “This democracy does not serve us, we need a better democracy,” he stated after criticizing the “corruption that April created.” Along with immigration, corruption is the other great pillar of the political battle of the Portuguese extreme right, which filled the country with posters promising to “clean up” politics. This morning he reiterated the message: “We have to clean up the corruption that April created, no matter who it hurts.”

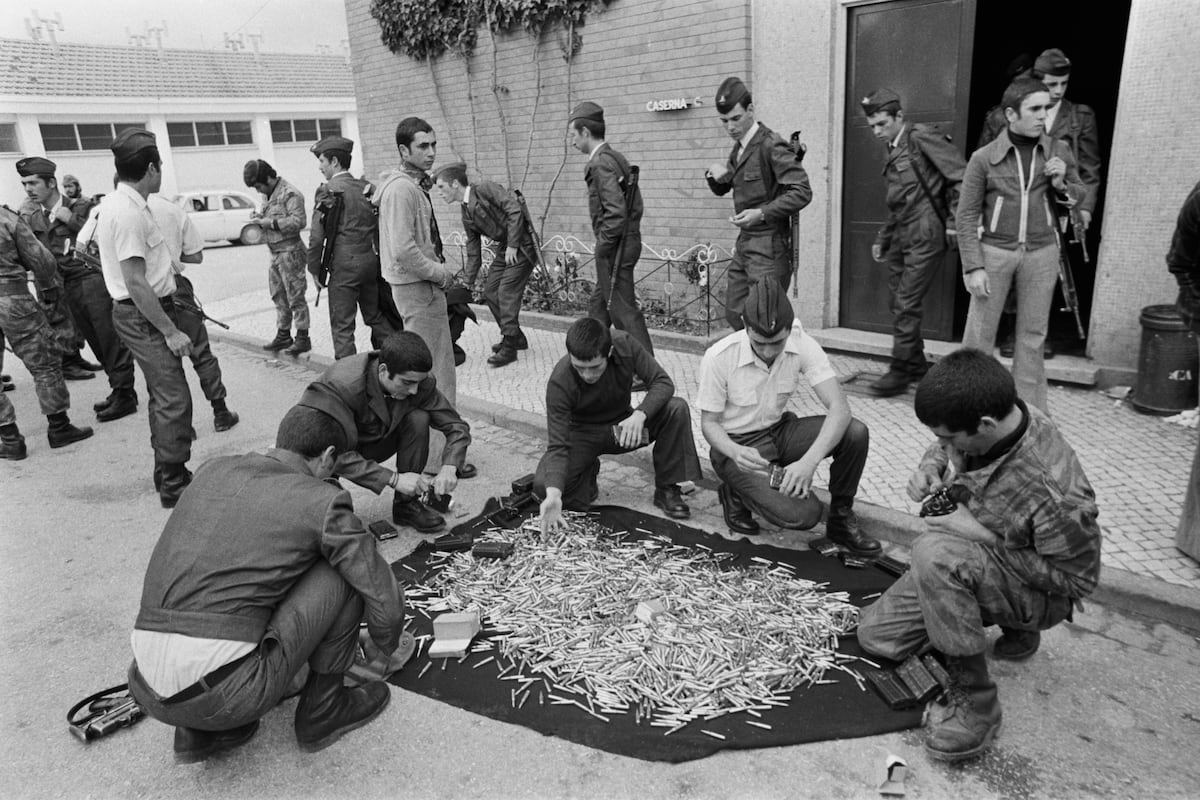

The commemorative session confirmed the division between formations when it came to interpreting that military operation of November 25, deployed by the April captains to put an end to the extremist drift that had taken the political process in the streets and in the barracks. The controversy over the format of the ceremony, as solemn as the one dedicated to April 25, when the dictatorship fell, was evident in the speeches and in the absences. None of the captains who carried out that operation attended the event, with the exception of António Ramalho Eanes, who would become the first Head of State elected in democracy backed by the prestige achieved on November 25 as author of the operations plan. This morning he sat in the authorities’ gallery next to another former president of the Republic, Aníbal Cavaco Silva.

Both the current president, Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa, and the president of the Assembly, José Pedro Aguiar Branco, made conciliatory speeches that tried to repair the rejection that the organization of this tribute has aroused in the ranks of the left. The Portuguese Communist Party boycotted the session and did not attend, while Joana Mortágua, the only Left Bloc deputy present, described it as “an exercise in historical revisionism” and “a nonsense that reveals the deplorable willingness of the PSD to give in to the extreme right.” Mortágua recalled, without citing them, that the Democratic and Social Center (CDS), a minority partner of the conservative coalition government and promoter of this Monday’s act, voted against the Constitution in 1976.

The Socialist Party, which was the main political ally of the April captains who mobilized on November 25, criticized that “the symbolic and scenic comparison with the founding date of the democratic regime is a path that reopens wounds healed long ago.” Its leader Pedro Nuno Santos did not intervene, but rather the deputy Pedro Delgado Alves. There were, in addition, numerous socialist parliamentarians absent.

Apart from words, gestures also spoke. On the left benches, the parliamentarians wore red carnations, a symbol of April 25. The deputy of the Social Democratic Party (PSD, center-right, in the Government), Miguel Guimarães, defended November 25 as the date that allowed “a liberal and pluralist democracy, freeing us from a popular democracy of Marxist inspiration.” Paulo Nuncio, promoter of this morning’s solemn session, intervened on behalf of the CDS, with appeasing words: “November was not made against April. What we celebrate here is not a counterrevolution. On November 25, he rescued the initial democratization plan.”

The President of the Republic, Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa, for his part, recalled that, in historical terms, April 25 is the “essential” day and that there is no “contradiction” between both dates. “April 25 opens a path towards freedom and democracy delayed by the revolution and November 25 takes a very important step on that path,” he indicated.