The 2022 Soccer World Cup was held in Qatar between the months of November and December, and with many matches at night to avoid the heat. The next world championship, 2026, will be held between June and July 2026 in Canada, the United States and Mexico. Now, a biometeorological report published in Scientific Reports warns that most venues have a high risk of excessive heat. In three of them, extreme thermal stress will continue until late in the afternoon, and could reach 50º. In a context of climate change, the authors maintain that measures will have to be taken to prevent footballers from lowering their performance or, worse, their health from deteriorating. In 2030, the World Cup will be in the summer of, among others, countries as hot as Morocco, Portugal and Spain.

A few years ago the International Federation of Football Association (FIFA) implemented a series of measures to ensure the health of players in extreme weather conditions. The best known is the hydration pause, when players approach the sideline to drink liquids for three minutes to replace lost water and salts. These breaks can be activated after 30 minutes of each of the two parts of the match if the temperature reaches 32º. But these degrees are not those indicated by a conventional thermometer, but rather by a more complex instrument with which the so-called wet bulb globe temperature index (WBGT) is created. By combining the temperature, relative humidity of the air, wind or solar radiation into a single value, it is considered to better reflect the apparent heat, that perceived by the organism. However, the authors of this new work maintain that the WBGT index does not really reflect the thermal stress of the players.

“Although FIFA recommends the use of the WBGT index to determine safety standards during a football match, it is considered an imperfect measure of the thermal load of athletes, as it tends to underestimate the level of thermal stress,” says sports physiology researcher at the University of Wrocław (Poland) and senior author of the study on the heat in the next World Cup, Marek Konefał. “The WBGT does not incorporate the most important factors specific to the sport, that is, the production of specific metabolic heat, the specific clothing worn by athletes and the effects of body movement on relative air speed,” he adds. Furthermore, this index would not correctly reflect the extra thermal load that is suffered when environmental factors such as high humidity or lack of air interfere with the main mechanism that humans have to contain temperature, sweating. For all these reasons, Konefal and his colleagues have proposed another indicator called the Universal Thermal Climate Index (UTCI), which in addition to collecting everything contained in the WBGT, adds parameters to model the response of the human body to heat. .

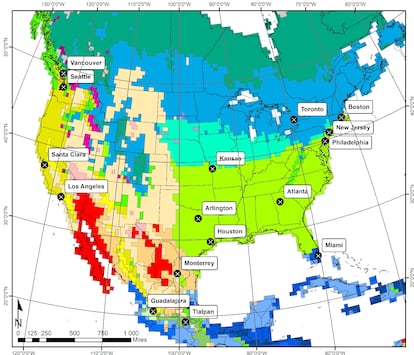

Based on this UTCI, 10 of the 16 planned venues for the next World Cup could put soccer players at risk of extreme heat stress, with the most dangerous matches being held in Arlington and Houston (both in Texas , United States) and Monterrey, in Mexico. The highest values of this stress will occur between 2:00 p.m. and 5:00 p.m. local time in all locations, except Miami, which advances and shortens its time slot until 11:00 a.m. and 12:00 p.m. One of the key factors will be dehydration. Based on the climate data recorded by the European Copernicus system in the months of June and July since 2009, the period of greatest risk will once again be the early afternoon. On the grass of the stadiums in Arlington, Houston and Monterrey, players could lose much more than a kilogram of sweat (essentially water) in an hour. The most benign locations would be those of Vancouver, in Canada, Seattle, in the United States, and Tlalpan, in Mexico City. The first two are far to the north, while the third is more than 2,200 meters above sea level.

“UTCI values do not correspond to exact air temperature data, as they reflect the impact of air temperature and humidity, wind speed, solar radiation, physical activity and clothing on the human thermoregulatory system and the heat exchange between the human body and the environment,” recalls Konefal. But, according to their calculations, in three venues, the aforementioned Arlington, Houston and Monterrey, they expect a UTCI of 49.5º until even six in the afternoon, which would generate extreme thermal stress in the players. However, the Polish scientist does not believe that these venues should be eliminated from the championship, “but as long as the match is played at an appropriate and safe time.” In addition to the need for air-conditioned facilities throughout the stadium, the scientist ends with a reflection that could be very timely, if not for this World Cup, then for the following ones: “Perhaps, taking into account the increase in global temperature, “The World Cup should definitely be moved to spring/autumn.”

The personal trainer and professor at the Faculty of Sports Sciences at the University of Murcia, Pedro Antonio Ruiz, remembers that in conditions of high temperatures and high humidity “we generate a lot of heat, but the ambient humidity prevents us from dissipating it.” And that is what is expected in many of the World Cup venues. “When both thermal conditions come together, the risk of dehydration and even the possibility of suffering from heat stroke increases exponentially, since, during a soccer match, it is very normal for soccer players to experience a loss of water between 2-3 % of body weight”, he details. Thermal stress begins at 24º-25º, “but playing at 35º, which will occur in many of these cities, is crazy,” adds Ruiz. Although those responsible for the championship are taking measures (such as extending cooling) and plan to schedule the matches taking into account the risk of excessive heat, this professor fears that high temperatures and high humidity will be “very present even in later hours, until 8:00 p.m.-10:00 p.m.

Another problem that Ruiz wants to highlight is height. With two locations at altitude, Tlalpan (at 2,240 meters) and Guadalajara (at 1,566 meters), “a period of acclimatization will be needed, if you arrive the day before, you will be at a disadvantage,” he says. This is because players or teams not accustomed to exercising at altitude, with less availability of oxygen, “will compensate for this deficit of O₂ in the air by breathing more intensely, suffering a forced decrease in performance during the match,” he details. For the professor, the practice of celebrating World Cups in two or three countries is not, from a health point of view, something bad in itself. But “he doesn’t understand the mix of this championship; “All three are contiguous countries, but with different climatic zones.” In fact, the 16 venues fall into nine different climatic zones.

David Jiménez Pavón, head of the MOVE-IT research group, at the University of Cádiz, explains what can happen in the body under conditions of high temperature and relative humidity: “What happens is that performance significantly decreases due to changes in different elements of physiology. Although a lot of hydration is maintained during sports practice, there is usually no time for the hydration ratio that is needed.” To maintain body temperature at its optimal level, “a very accelerated process of sweating, hemoconcentration, and elevated heart rate occurs… in short, the anaerobic metabolism is more activated,” he adds. This, he adds, “generates more lactic acid, which is clearly associated with the earlier appearance of fatigue in performance.” Jiménez defends the need to carry out prior tests on the condition of the players: “It would be highly recommended for athletes and footballers to expose themselves to thermal stress performance tests to see individually how they respond and how they adapt to these physiological demands in high competition” .