The Moscow-Pyongyang axis worries the Asia-Pacific region. North Korea’s direct involvement in the Ukraine war, and the increasingly rhythmic dance between Russian President Vladimir Putin and North Korean leader Kim Jong-un, sends seismic waves from Europe to the other extreme of the great land mass. If the presence of elite North Korean soldiers in live-fire combat in Ukraine, already confirmed by kyiv, represents “a significant escalation” of the war on the Western Front, as defined by NATO, on the Asian flank the possible transfers are of particular concern. technological advances from Moscow to Pyongyang in the ballistic and nuclear fields, due to their potential to destabilize conflicts already entrenched in the region, such as that of the two Koreas or Taiwan. The dismissal of South Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol, after his aborted attempt to impose martial law, adds another element of uncertainty and instability that benefits the interests of the Russian-North Korean axis.

For Kitamura Toshihiro, director general of Press and Public Diplomacy at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, the fact that there are North Korean soldiers on the Russian front is “a clear example” of how “interconnected” the security threats in Asia and Europe are. The concern goes beyond Pyongyang receiving high-quality Russian technology: “If North Korean soldiers return, they will do so with real combat experience,” he warns. It is something that has not happened since the Cold War: North Korea has not participated in a direct war since the one it fought against South Korea between 1950 and 1953; The South Koreans have not done so since they sent troops between 1964 and 1973 to the Vietnam War (1955-1975).

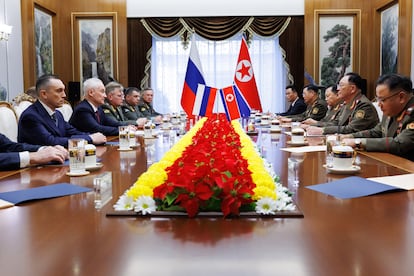

“Everything is getting mixed up,” says a European diplomatic source based in Beijing. kyiv and Seoul confirmed casualties of North Korean soldiers in the Russian province of Kursk weeks ago, after the firing of British Storm Shadow missiles; At least 100 soldiers from the Asian country have died and a thousand have been wounded, according to a South Korean parliamentarian this week after being informed by Seoul’s intelligence services. For the European source, the new alliance between Kim and Putin, sealed in June and in force since the beginning of December, implies even a greater security risk than the Russian leader’s redoubled nuclear threats. This “strategic partnership agreement” includes a pact of “mutual defense in case of aggression.” Putin and Kim do not hide their good harmony either. The Russian’s last gesture to thank the ammunition and the troops was to give the Pyongyang Zoo more than 70 animals, including a lion, two brown bears, two yaks and five cockatoos.

South Korea interprets North Korean involvement in the Ukraine war as a direct threat to its security. “We do not rule out the possibility of supplying weapons. We would give priority to defenses,” South Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol announced in early November, when he was still in charge of the country. It is something that until now had not been done, limiting itself to non-lethal aid parties. A week before decreeing martial law, the South Korean president met in Seoul with a Ukrainian delegation led by the Minister of Defense, Rustem Umerov, before whom he emphasized the commitment to seek “practical response measures” and with whom he agreed to “continue sharing information on the deployment of North Korean troops and the transfers of weapons and technology,” according to the official statement.

The debate, according to Ramón Pacheco Pardo, a professor of International Relations at King’s College London specializing in Korea, was whether Seoul would decide to transfer its anti-missile shield system to Ukraine and even its weapons. The consequences of this “more direct involvement” are unpredictable. The Kremlin warned Seoul, through Andrey Rudenko, Deputy Foreign Minister, to “seriously evaluate the situation” and to refrain “from taking reckless steps,” according to the Russian Tass agency. Sending weapons that kill Russian citizens, he indicated, would destroy relations between both countries. “We will respond in any way we deem necessary,” he threatened.

The political crisis that has shaken the South Korean country has frozen the debate. Yoon, dismissed last Saturday by the National Assembly, has been removed from power, pending the Constitutional Court’s ratification of the decision. Meanwhile, Prime Minister Han Duck-soo, the state’s second highest authority, has assumed presidential duties. “The South Korean government is functioning, but new initiatives are paralyzed. Whatever was going on, it’s not going to happen until this whole impeachment process comes to a resolution,” says Chun In-bum, a retired three-star general in the South Korean army and an expert on military affairs. “This, in turn, will benefit the Russians and the North Koreans,” he says. They will save time. In his opinion, South Korean political instability is bad news for Ukraine, for Europe and also for Asia. He considers it likely that South Korea’s political and military rapprochement with Japan, led by Yoon, under the auspices of the outgoing US president, Joe Biden, will also suffer.

The situation coincides with an already turbulent time between the two Koreas. In October, Pyongyang approved a reform of the Constitution that omits references to reunification with its neighbor, which it now defines as “the main hostile and enemy state.” In January, the all-powerful Kim had demanded from Parliament that the constitutional text include the idea of “completely occupying, subjugating and claiming” South Korea and “annexing” it in case a war broke out on the peninsula. At the end of November, the North Korean supreme leader declared that “never” has the confrontation between both parties “had been so dangerous and intense, capable of escalating to the most destructive thermonuclear war,” reported the state agency KCNA.

A recent article by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace think tank highlights that “Ukraine is evolving into an unexpected indirect battlefield for tensions on the Korean Peninsula.” “The Ukrainian theater of operations risks becoming the first direct test of Korean military capabilities since the 1953 armistice, which could radically alter the security balance of the peninsula,” the text warns.

Analyst Pacheco Pardo is also concerned about how the growing rapport between Putin and Kim could influence other potential regional fires. If, for example, there were an eventual conflict over Taiwan, the self-governed island that Beijing considers an inalienable part of its territory, the North Korean regime could take advantage of it to create instability with its southern neighbor. “Once North Korea has helped Russia,” he points out, that hypothetical conflict between the two Koreas would cause “Russia to be forced to support North Korea,” something that perhaps would not have happened before the June pact. Pacheco Pardo does not believe it is likely, but, after seeing how Russia invaded Ukraine, it cannot be ruled out that this gives China “ideas,” he explains, observing the absence of support from third countries.

It is an eventuality that also worries the country of the rising sun. “We are concerned about the cooperation between China and Russia,” concedes Toshihiro, from the Japanese Foreign Ministry, as well as the “growing assertiveness [de Pekín] in the South China Sea, especially around Taiwan.” However, Kyoko Hatakeyama, professor of International Relations at Niigata Prefectural University, emphasizes that North Korea and China “are different” and recalls that, for the Chinese Government, economic development is fundamental, which is why You cannot take such a decision lightly. “North Korea is not a permanent member of the UN Security Council nor a major player in international organizations. China cares about its reputation as a major superpower; to North Korea, no,” he adds.

China, which wants to protect its ties with the United States and the European Union, is juggling to maintain, for the sake of the gallery, a balance sufficiently far from the Pyongyang-Moscow axis. However, North Korea’s entry into the Russian front—after all, an event that upsets Washington—“is not so bad for Beijing,” explains Lee Sung-yoon, an international researcher at the think tank Wilson Center. “China’s biggest strategic competitor is the United States and counting on the influence that China has over North Korea [es su principal sostén económico] It already represents a huge advantage when negotiating,” says this South Korean analyst. “Beijing is looking for the right moment to show itself as a less radical nation and more inclined to peace than Russia and North Korea, but at the end of the day it is the benchmark for this group of autocracies,” Lee considers.

This cocktail of latent tensions, added to the growing Korean involvement in a conflict that takes place 7,000 kilometers away, highlights how regional dynamics are acquiring a global dimension. “The United States is more willing to get involved in the Indo-Pacific than in Ukraine,” says General Chun. “North Korea has escalated the scope of the war in Europe and this has made Europe and its allies more aware that North Korea is not just an East Asian problem, but a global one,” he concludes.