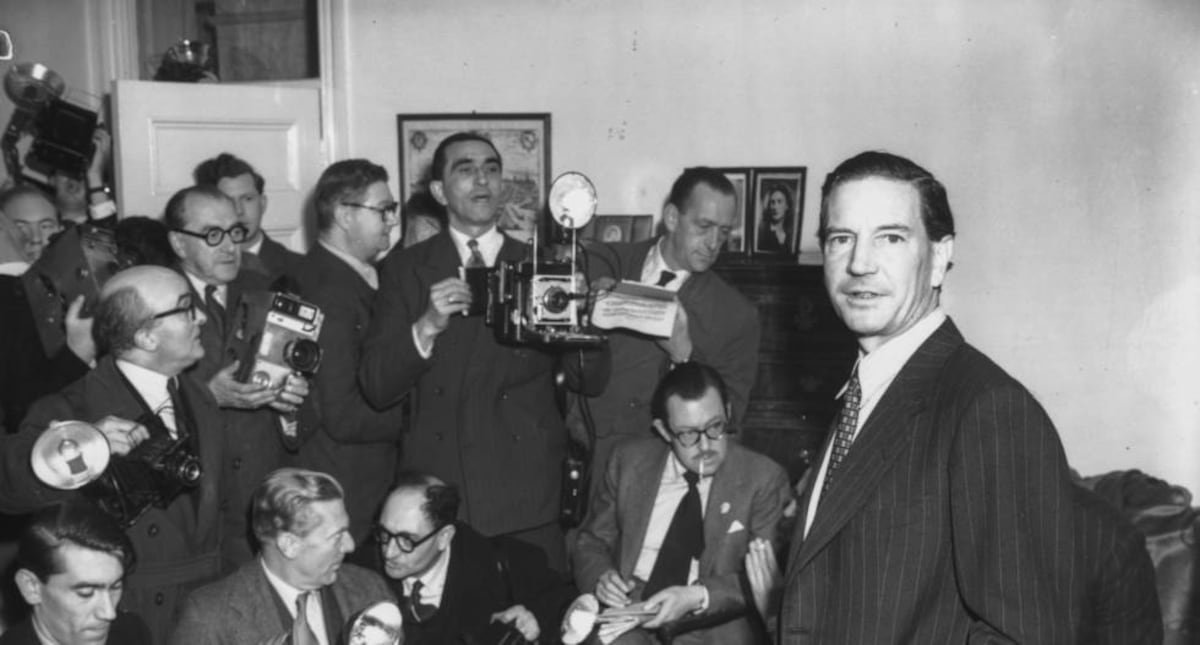

He was always the most intelligent and cunning of them all. They were called The Cambridge Five. Young British educated among the elite who, during the decades before and after World War II, would function as Soviet agents infiltrated at the heart of the system. Harold Adrian Russell Philby, known as Kim Philby was the most elusive, and the one who lasted the longest until being discovered. New documents made public by MI5, the United Kingdom’s internal security service, now reveal the latest secrets of the double spy who has provoked the most admiration and hatred among his compatriots.

There are 21 files that recount the recruitment of young Philby by the Communist International; his cold maneuvers to kill the defected KGB agent Constantin Volkov and his wife, before they betrayed him, or the hours of conversation in Beirut with his friend and colleague, Nicholas Elliott, in which he ended up confessing his decades as a spy for Moscow .

Marissa Davison (REUTERS)

The documents, however, do not reveal the final secret: why Elliott gave his old friend enough time to flee to the Soviet Union before being detained. Philby died in Moscow, revered as a hero by the USSR, but alone and drunk, 25 years later.

Kim of India

Philby was born in 1912 in Ambala, the Indian city that was then part of the British Raj. His father, John Philby, was an army officer, diplomat, explorer and writer who eventually converted to Islam and served as an advisor to King Abdelaziz bin Al Saud of Saudi Arabia. The nickname Kim, chosen by his father, is the title of Rudyard Kipling’s novel that tells the adventures of a young Indian who spies for the British Empire.

He studied History and Economics at Trinity College, Cambridge, where he was seduced by Marxism. Recruited by the Viennese branch of the Comintern (the Communist International), Philby carried out tasks for the Soviet intelligence service in Austria and Spain. Masked as a newspaper journalist The Timesmanaged to seduce the forces of the future Spanish dictator, Francisco Franco, with a series of reports favorable to the cause of the coup plotters. He personally received the red cross for military merit from Franco himself.

Philby’s hours of conversation with Elliott, undoubtedly the most revealing material of all the information made public by MI5, show a man damaged by decades of lies and concealment, who is sparing and evasive when it comes to admitting his betrayals. , and continues to play with ambiguity and half-truths, despite confessing his status as a double agent.

In 1945, when Philby was already immersed in the British foreign spy service, MI6, and working full capacity for the KGB, he learned that a Soviet agent, Volkov, had appeared at the British consulate in Istanbul, where he offered a sum A wealth of information and secrets was exchanged for £50,000 and the chance to start a new life in the United Kingdom with his wife. Volkov was going to reveal the names of nine moles Soviets infiltrated the main institutions of the United Kingdom. One of them, he pointed out, was in charge of the MI6 counterespionage service. It was obviously Philby.

After notifying his bosses in Moscow, he traveled directly to Istanbul to take care of the matter. Upon arrival, Volkov and his wife had already been kidnapped, drugged, hidden with bandages and carried on a stretcher by a doctor and two KGB officers to a plane that took them to Bulgaria. They were never heard from again. “Presumably, the information you provided to the KGB was that which was of direct interest to them, such as the Volkov affair, right?” Elliott asked Philby in their meeting. “Of course,” the double agent confirmed laconically.

The other spies

Despite the years of university friendship and subsequent camaraderie, Philby always tried to protect his own back against the risks and clumsiness of Guy Burgess, Donald Maclean, Anthony Blunt and John Cairncross, the rest of the agents who made up the Cambridge Five.

Donald Maclean, son of the Liberal Party politician of the same name, became first secretary of the British embassy in Washington between 1944 and 1948. There he carried out the most important work for the Soviet Union. A large part of the communications between British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and American President Franklin D. Roosevelt passed to Moscow, and, later, between the new British head of government, Clement Attlee, and Harry S. Truman, head of the North American Administration. . The Soviets learned through Maclean of the United States’ progress in manufacturing the atomic bomb.

When Maclean returned to the UK, it was Philby who ended up posted to the US capital. And there he discovered that the British authorities were about to unmask his former comrade. Using a secret code, he notified Guy Burgess, another of the five spies, who worked at the Foreign Office and lived at the time in Philby’s London apartment, to notify Maclean. The key agreed upon between the former friends was to refer to an alleged abandoned car in the backyard of Philby’s residence. “If I am forced to face complications as a result of the vehicle problem, I intend to pass on very high costs to you…” Philby wrote to Burgess. The letter is part of the documents now revealed by MI5.

The confession

Despite growing suspicions regarding Philby from his British superiors, they failed to discover anything. Although he was forced to leave MI6, it was precisely his friend Elliott who helped him settle in Beirut, the capital of Lebanon, in 1956, as a correspondent for The Economistand of The Observer. Six years later, her friend Flora Solomon’s confession that Philby had tried to recruit her as a Soviet agent in 1934 finally unmasked the double spy.

Elliott traveled to the Lebanese capital and recorded the conversation with his friend for several days. “I certainly wouldn’t have talked to anyone else,” Philby admitted. “When you told me that you yourself had begun to believe all the evidence accumulated against me, it was clear to me. I have been waiting for this moment for 28 years. Here’s the exclusive,” Philby confessed to Elliott.

The two friends said goodbye with the promise that Philby would continue to provide information to Peter Lunn, MI6’s man in Beirut. There was a tacit understanding that there would be no criminal prosecution if the double agent confessed to all his betrayals. A few days later, Philby fled to Moscow aboard a Russian cargo ship docked in the port of Beirut. “I can’t help but think that, in some way, you wanted me to escape,” he wrote years later from the Soviet capital to his old friend Elliott.