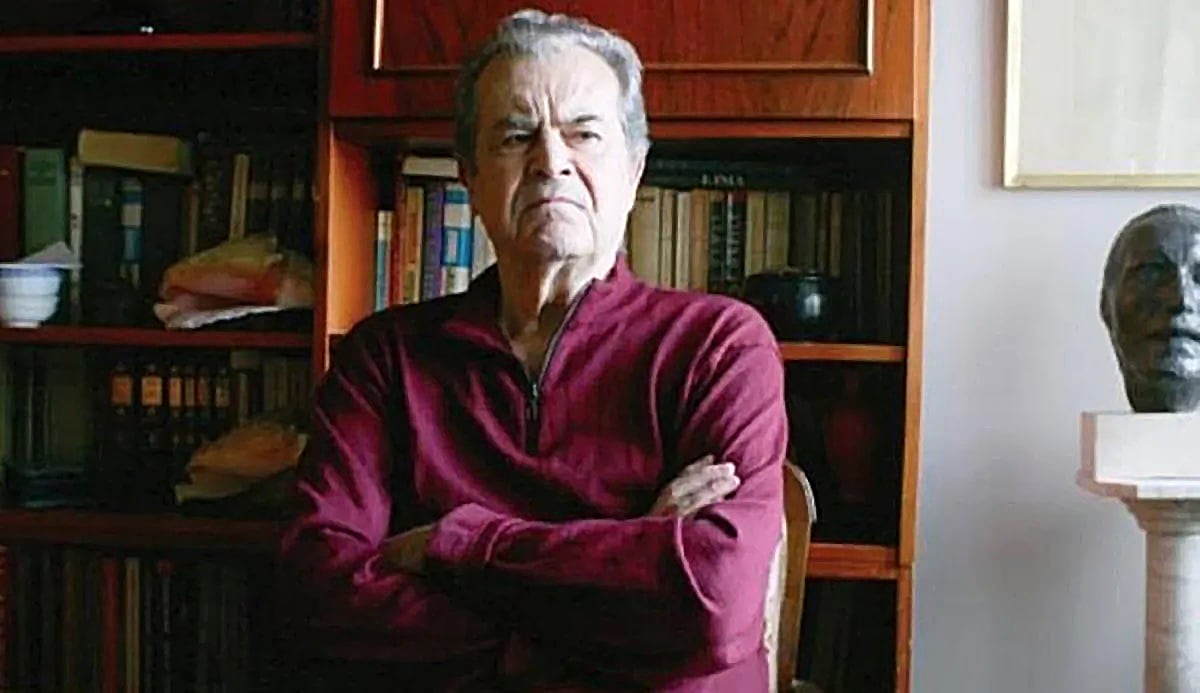

Dumitru Popescu, one of the most prominent figures of the Romanian communist leadership and one of the last members of dictator Nicolae Ceausescu’s team, died last Friday at the age of 96 in his home in a working-class neighborhood of Bucharest almost 35 years after the overthrow of the regime. The writer and journalist, recognized as the architect of the satrap’s cult of personality, outlined the rules of his country’s literature, with the aim of praising the figure of the ‘Conducator’, who also liked to call himself ‘the beloved son’. , ‘the genius of the Carpathians’ or ‘the Thought of the Danube’. He even compared the autocrat with Pericles, Napoleon Bonaparte and Abraham Lincoln.

The ideologue became the iron hand that controlled the press in Romania after the Caesarism imposed by Ceausescu after his visit to China and North Korea in 1971. Upon his return from the Asian tour – the North Korean leader Kim Il-sung organized a spectacular ceremony in his honor at the Moranbong stadium in which some 120,000 people participated – the autocrat complained about the speeches “abstract” statements that were made in their country without actually explaining the government’s achievements to improve the lives of the people. To do this, he introduced political culture into education, a task that fell to Popescu. It was at this moment when he entered the immediate circle of power that began to outline the president’s melomania and began to write Ceausescu’s speeches and praises for him.

Popescu was nicknamed God for his severity towards his subordinates. According to Ioan Morar, novelist and journalist who founded the magazine Catavencu Academy(Thursday Romanian), at a party meeting with journalists in the Scanteii House – a building similar to that of Moscow State University that housed the official newspaper of the Romanian Communist Party and is now called the House of the Free Press – , said: “I am your father, I am your mother, I am your God.”

Popescu graduated in 1951 from the Faculty of Economic Sciences. However, he debuted as a journalist during his student days (in 1950), in the magazine Contemporary (The contemporary), a profession that he never abandoned. In 1956, on the occasion of the preparation of the Congress of the Union of Young Workers, Ceausescu invited him (although both had not met before) to take over the position of editor-in-chief of the youth newspaper. Scanteia (Chispa in Spanish), where it remained until 1960.

He ran Agerpres, the national press agency, for two years, a position he left to become Minister of Culture. In 1965, he returned to journalism, this time as editor-in-chief of Scînteiawhere he worked until 1968. He had joined the Romanian Workers’ Party in the early 1950s and became a member of the Central Committee of the Romanian Communist Party in 1965, where he remained until the fall of the dictatorship. In addition, he was appointed secretary of the Central Committee in 1968 and a year later included in the select group of the Executive Political Committee of the Central Committee, in addition to being a deputy of the Grand National Assembly from 1965 to 1989. And in the last eight years of the regime he They appointed rector of the Stefan Gheorghiu Academy in Bucharest, a school specialized exclusively in the training of communist leaders.

His figure as part of the communist elite deeply marked the history of the country. Under the leadership of the Romanian Communist Party, between 1947 and 1989, society was subjected to strict centralization, state propaganda and totalitarian control. Forced industrialization, the collectivization of agriculture and censorship shaped daily life, which the dictators Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej and Nicolae Ceausescu consolidated with a repressive regime.

Historians define him as one of Ceausescu’s closest collaborators and an introverted person whose private life was barely known. He did not have close relationships with anyone and maintained limits on communication at work. He described surprises as undesirable and despised any form of seduction, placing it outside the rigors of politics and the behavior of the communist militant. He trusted in the authority of his position, in the duty of his subordinates to comply, and in the fact that his strategy was capable of mobilizing citizens. During democratic Romania, Popescu dedicated himself to writing several books about his memoirs with titles such as: “I was also a carver of chimeras” or “Cronus devouring himself”, among others. However, specialists regret the superficiality of his texts.

“An important contribution to the creation of the Ceausescu myth was made by Dumitru Popescu, an arrogant apparatchik [tecnócrata del partido] who held the position of secretary of the Central Committee on cultural and ideological issues for almost 15 years. Popescu considered himself a novelist, but his publications were ridiculous attempts at apologetics for the party,” describes Vladimir Tismăneanu, author of the report on the communist dictatorship on which former president Traian Basescu based his condemnation of the regime in 2006 as “criminal” and “ illegitimate” in Parliament. The political scientist called him “the great pontiff of political religion.” ceausista”.