The leaders of the BRICS+ group are holding a summit these days in the Russian city of Kazan that takes place the same week in which the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank (WB) hold their annual conference in Washington. Coincident or not, the coincidence underlines the underlying tension between the BRICS+ and the Western bloc that has shaped the post-war world order after the Second World War, and of which the Bretton Woods institutions are a symbol. The BRICS+ demand a new order, and that demand is essentially directed at the advanced Western economies grouped in the G-7. Given this scenario, it makes sense to ask what the relationship of forces is between the two groups.

The answer to that question is complex. Without a doubt, it is possible to x-ray economic or demographic data that illustrate some measures of the size of each of the groups. The recent expansion of the group of emerging countries that has added new members (Iran, Egypt, Ethiopia, United Arab Emirates) to those already established (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) has increased its weight. The G-7 remains in the same perimeter since Russia left in 2014 (USA, Canada, Japan, Germany, United Kingdom, France and Italy, joined by the Commission and the Council of the EU). This type of comparison offers interesting interpretation keys.

The combined GDP of the BRICS+ is still lower than that of the G-7 – 26% of the world total compared to almost 43% – but exceeds it if calculated with purchasing power parity – 35% compared to almost 30% —, according to IMF data. The demographic superiority is evident – 43% of the world population compared to approximately 9% – and so is the availability of energy resources, especially if the incorporation of Saudi Arabia is formally confirmed.

In trade terms, the G-7 continues to be superior, with exports of goods and services that add up to 31% of the world total, compared to 17% for rivals, according to WB data. Western domination in the monetary sector is also evident, in multiple domains, such as reserves or use in international transactions.

However, although useful, these data and other similar ones are insufficient to assess the real weight of the two groups. A political assessment is essential. In this key, the lack of internal cohesion in the BRICS+ stands out strongly and crucially. This grouping is not an alliance and it is very questionable whether it can even be classified geopolitically as a bloc.

The group does have a common denominator, which is criticism of the world order created by the West and which they consider not representative of the current world. On that basis, its members have activated two mirror institutions to the IMF and the WB: the new Development Bank and the Contingent Reserve Fund. But neither of them has really taken off, and other initiatives that have been proposed over the years are in a larval state or not even that. De-dollarization efforts have, so far, yielded modest results.

The political reality is that behind this criticism of the Western order lies a schism: on the one hand, those who champion positions antagonistic to Western forces, such as China, Russia or Iran. On the other hand, members who have no interest in this antagonism and who choose active non-alignment; This is the case of India, Brazil or South Africa.

The geopolitical schism is the central element of the difficulty in moving from criticism to action. But the group’s heterodoxy is great in other concepts as well. Some members are democracies—generally non-aligned; others, dictatorships—generally antagonistic to the West, and majority after enlargement. Some have modern economies with manufacturing capabilities; others, backward or simply extractive. Furthermore, there are serious internal animosities between members, such as between Egypt and Ethiopia, Iran and Saudi Arabia, or China and India. Although in the last two cases there have been signs of thawing, the underlying geopolitical tension persists.

For all these reasons, the rejection of the current order is a powerful collagen that keeps the group alive and gives projection, although the implementation of policies that build a true alternative seems unlikely.

Political differences

The G-7 has features comparable to the BRICS+, such as lacking a formal nature, having a hegemonic country – the US in one case; China on the other― and having been born as a forum eminently dedicated to matters of an economic nature. In political terms, the G-7 shows important differences with respect to the other.

The first is that, although it is in itself an informal grouping, it is based on a solidly structured underlying framework of formal relationships. Six of the seven members are part of NATO. The one that does not, Japan, in turn has a bilateral defense treaty with the United States, leader of NATO. Three are also members of the EU, which, together with the presence in the group of community institutions, offers – although without guarantees – the potential of a transmission belt for decisions to another structured and vigorous entity. Furthermore, the G-7 has a great capacity to influence institutions such as the IMF or the WB, much more consolidated than their BRICS+ alternatives. The structural reality that accompanies the G-7 has, therefore, a framework that allows many more real options for action.

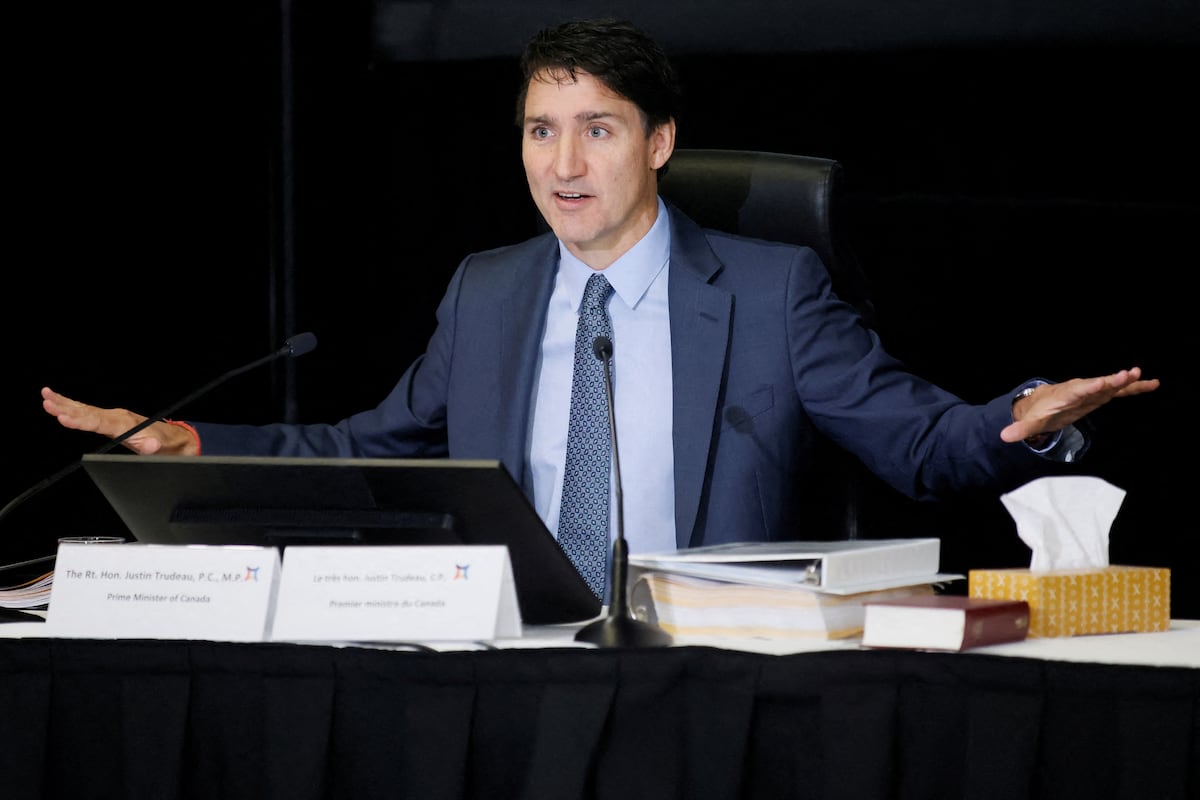

Furthermore, during Joe Biden’s presidency in the United States there has been a situational reality that has provided considerable political cohesion to the G-7. Especially in the last two years, the group has gone beyond its traditional territory of political-economic approaches to address geopolitical, technological or other issues with strategic value. In this way, it has tried to emerge as a driving force to define the positioning of the Western world. Especially with respect to the war in Ukraine, the group has maintained evident cohesion and launched concrete actions, such as the coordinated delivery of $50 billion to kyiv taking advantage of the interests generated by the funds frozen to Russia. The initiative has encountered obstacles, but is on its way to fruition.

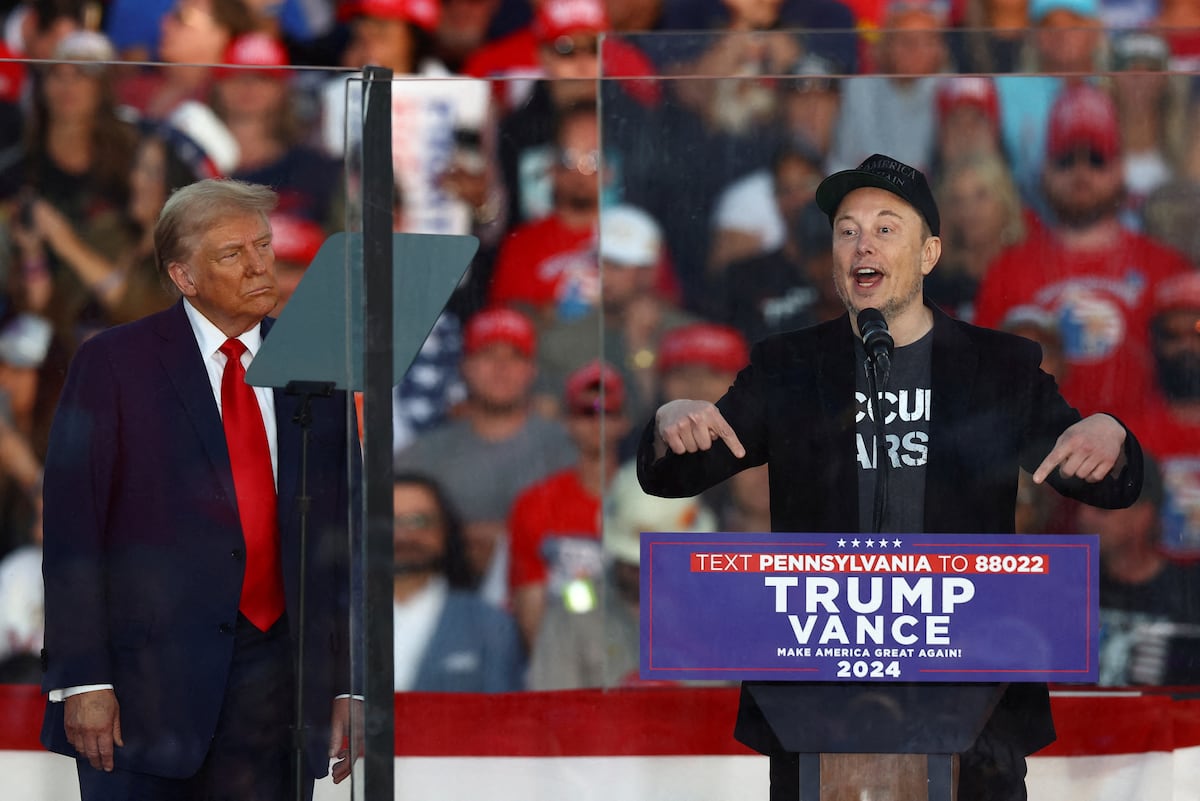

This current reality, however, could be broken in the event of Donald Trump’s victory in the US elections on November 5. It is more than likely that the magnate’s return to the White House dynamited the group’s cohesion features and widened the existing gaps, which the G-7 has traditionally tried to suture or overcome.

European partners and the Biden Administration have had serious internal disagreements over protectionism or how to handle the rise of China. Despite this, everything has flowed in these four years within a constructive framework. This could change and open a schism within the G-7 similar to the one that tears the BRICS+ apart and makes the construction of common and truly transformative projects unlikely.